Insights > Sustainable Urbanism and The “15-Minute City”

Sustainable Urbanism and The “15-Minute City”

The following sustainable urbanism case studies display the type of vibrant environments that can be fostered by a bold approach to neighborhood building, with a focus on walkability, sustainability, mixed-use and flexibility, and a diversity of housing types and incomes.

A recurring theme with these projects is the idea of a “15-minute city,” a term used to describe areas where residents can meet all of their basic necessities within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. The “basic necessities” usually include grocery stores, schools, medical facilities, parks and places for public leisure, culture centers, and reliable transit.

The idea is intrinsically sustainable and serves as the antithesis to current zoning, creating local ecosystems and deconstructing the idea of a city parsed up into defined districts. In addition, in order to cultivate a “15-minute city” equitably, workers must have the option to be residents, and vice versa, which brings on the need for a diversity of housing types for a mix of incomes.

Traditional mid-rise buildings have the lowest embodied and operational energy per unit of housing and vastly lower transportation-related costs and carbon emissions. Additionally, they allow for the best land conservation practices, using ~ 1/10 – 1/20 of the land as compared to most current development in the West.

The long-term goal of a 15-minute area is not necessarily to grow; rather, the idea is to have the built-in flexibility to adapt over time. As far as growth, ideally these areas are not isolated in their ability to meet the parameters of a 15-minute city. As the name implies, the hope is for the concept to spread throughout a city’s existing fabric, within its boundaries – used as a yardstick to identify where necessities are lacking – so that eventually one could drop a pin anywhere on a map and see that the criteria for a 15-minute city are met.

Recent Posts

- Ideas at Play: How Adults Can Design for Children November 25, 2025

- Designing for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities November 18, 2025

- Trauma-Informed Design: Inclusive Buildings for All November 11, 2025

- Neuroscience and Architecture: What Science Teaches Us About Designing Buildings for Mental Health and Well-Being November 4, 2025

- Human-Centered Design: Making the Built Environment Work for Everyone October 28, 2025

The included projects are intentionally more recent examples, meant to demonstrate that sustainable urbanism is achievable in modern times. History has provided examples of, arguably, better urbanism and neighborhood design. In order to continue to improve current efforts, it’s essential to look to the urban core of many of these cities for inspiration. These neighborhoods foster community, health, and resiliency. Intentional design of the commons is what will make them thrive.

BedZED (Beddington Zero Energy Development)

Wallignton, UK | 2002 | Bill Dunster Architects

Unique Features

BedZED was the first large-scale mixed-used sustainable community in the UK. The project focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and water use. An on-site car share program encourages residents to not own a personal car and makes more car-free pedestrian-friendly open space for residents to enjoy.

Key Elements

- Built with local materials and reclaimed products

- Solar heating

- High insulation

- Wind cowls

- Solar panels

- High-efficiency water-saving appliances

- Public and private green space

- Low energy costs

The Kalkbreite Cooperative

Zurich, Switzerland | 2014 | Muller Sigrist Architekten

Unique Features

The Kalkbreite Cooperative is a mixed-use development established over a train depot, which functions as a key connector in the urban fabric of the neighborhood. The commercial spaces include a cinema, restaurants, bars, a day care, and several stores and offices. The residential portion is a cooperative that offers a vast range of living units, from clusters of single units to 17 room-shared flats, in order to suit the changing needs of anyone who would wish to live in Kalkbreite.

Key Elements

- 11-room guesthouse

- 7 rentable flex rooms

- 26,900sf green courtyard

- 16,146sf terrace and rooftop gardens

Grow Community – The Village

Bainbridge Island | 2014 | Davis Studio Architecture + Design, LLC

Unique Features

Grow Community is the largest solar community in Washington. Parking is limited to one space per household and is not located immediately next to the units, thereby encouraging residents to walk or bike.

Key Elements

- Net zero

- Net positive

- High insulation

- Airtight construction

- PV panels

- Community gardens

- Orchard

- Woodlands

- Open green space

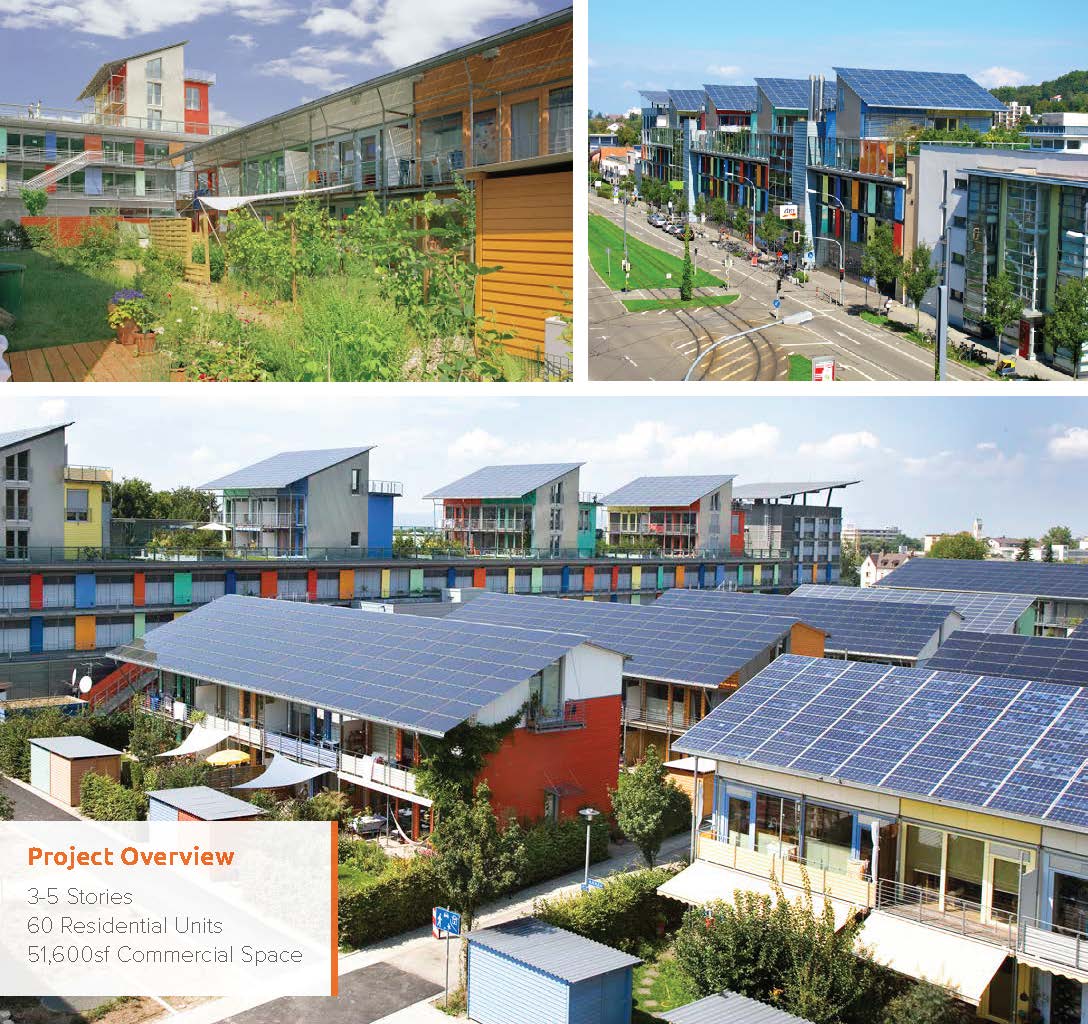

Sonnenschiff and Solarsiedlung

Freiburg, Germany | Summer 1998 | The Courtyard Group / Artian Construction

Unique Features

The Solar Settlement is made up of its commercial half, Sonnenschiff (Solar Ship), and its residential half, Solarsiedlung (Solar Village). The settlement is located in the Vauban District, which is known globally as one of the most sustainable urban developments.

Key Elements

- Built according to Passive House specification

- Photovoltaic system installed on roofs

- Natural air-conditioning

- Latent heat storage

- PlusEnergy approach

The Village on False Creek

Vancouver, BC, Canada | 2010 | Merrick Architecture

Unique Features

The Village on False Creek is a brownfield redevelopment that was originally designed as Vancouver’s Olympic Athletes’ Village for the 2010 Games. The complex is meant to encourage a diverse and vibrant neighborhood community, with a mix of residential, commercial, and community amenities along with public plazas and green spaces.

Key Elements

- LEED Platinum

- Green roofs

- Efficient energy and stormwater systems

- Community center

- 3 childcare centers

- A school

- Community garden

- Public plaza

GWL Terrein Housing Development

Amsterdam, Netherlands | 1998 | See Sources

Unique Features

GWL Terrein is Amsterdam’s oldest eco-district. The site was a heavy industrial area but has been transformed into a car-free, environmentally friendly residential area. Owners occupy half of the units, and the rest are social housing for rent. Of the units sold, two-thirds were grant-aided, with nearby residents given priority in applying for a home. Commercial uses include a gym, offices, and Grand Café Amsterdam.

Key Elements

- Environmentally friendly materials

- Dedicated cogeneration plant (combined heat and power) for the district

- On-site gray water collection

- Abundant green spaces

- Underground waste collection

- Limited car access and car sharing

- Adaptive reuse of industrial buildings

Titletown District

Green Bay, WI | 2017 | Rossetti

Unique Features

The Titletown District combines retail, recreation, and residential into one hub for Green Bay. The project is centered on a sloped building that doubles as a sledding hill, with a skating rink surrounding. In the summer, this transforms into a public park, making the site popular year-round.

*Phase 1 was completed in 2017. Phase 2 is under construction as of early 2020.

Key Elements

- Green roof sledding hill

- Skating rink

- 40-yard dash area

- Playground

- Full football field

- Hotel, flats, and townhomes

Pierhouse & 1 Hotel Brooklyn Bridge

Brooklyn, NY | 2017 | Marvel Architects

Unique Features

The primary goal of the Pierhouse development was for the building to function as an extension of Brooklyn Bridge Park and serve as a welcoming and porous connection between park and city. This is done through the inviting gesture of a 3-story archway, along with a program that engages the public on all sides, including the hotel entry, restaurant, café, spa, and events space. The residential units are similarly connected to both park and city, with Juliet balconies and a unique floor-through design that provides each unit with east and west views and sunlight.

Key Elements

- Green roofs

- Skip-stop circulation

- 195-key luxury hotel

- 300 parking spaces

- 2 restaurants

- Retail

- Park offices

- Rooftop pool

- 17,000sf event space

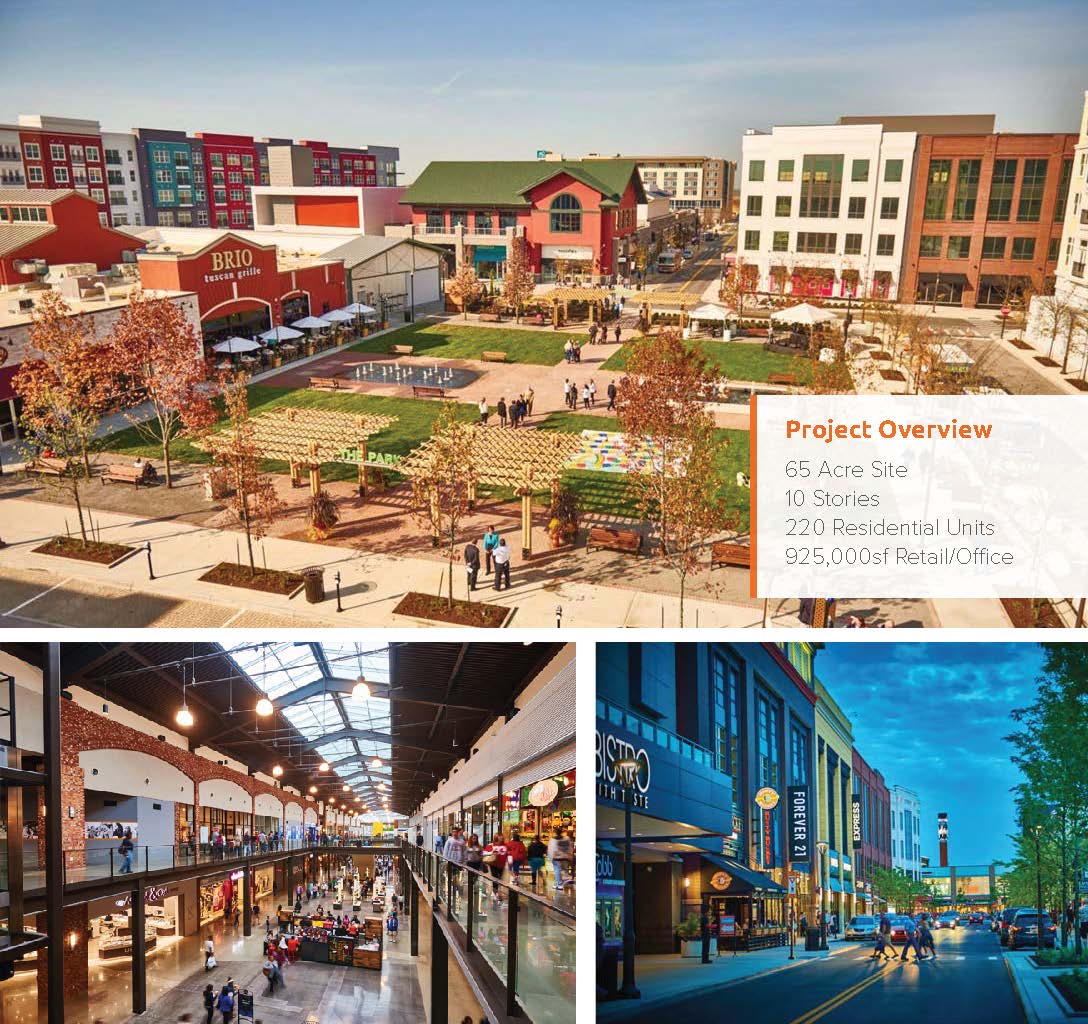

Liberty Center

Liberty Townshop, OH | 2015 | Torti Gallas & Partners

Unique Features

The Liberty Center is a mixed-use development centered outdoor spaces. The site’s design incorporates immersive experiential design in order to draw people in and encourage exploration. This element, combined with all the amenities provided, makes the Liberty Center a very popular destination.

Key Elements

- Public plazas that can host performances and events

- Rooftop plaza

- 632,000sf retail

- 16-screen cinema

- 62,000sf restaurant and dining

- 72,000sf office space

- 150-room hotel

- Interactive fountain and splash pad

- Public art

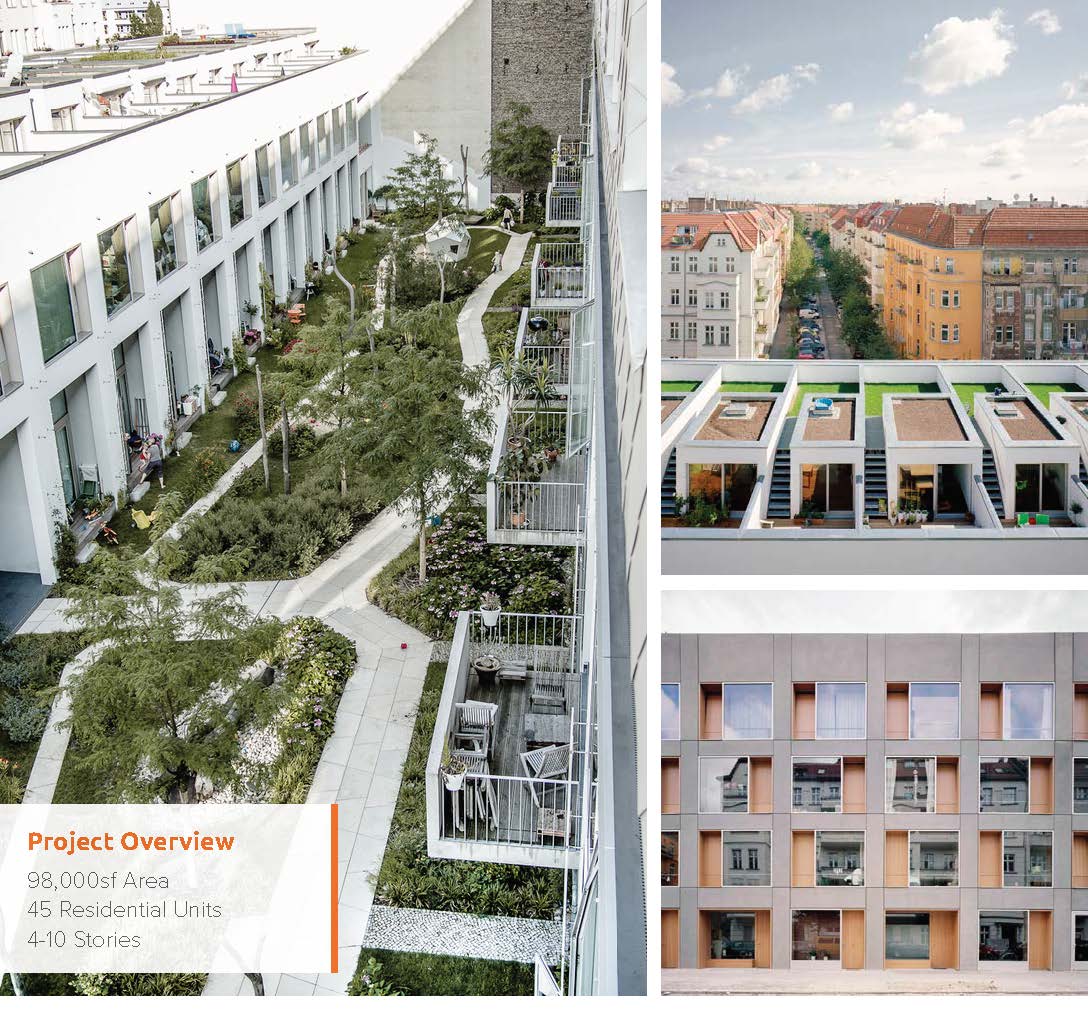

BIGyard

Berlin, Germany | 2010 | Zanderroth Architekten

Unique Features

The BIGyard development is meant to compact the feeling of a village into one block. Townhouses and penthouse all have separate entrances, while the paths to get to those entries interweave with others, leading to neighborhood-like causal interactions. Townhouses that open on the street are set up to function as small business storefronts or can be purely residential.

Key Elements

- 14,000sf communal yard

- 2,600sf common roof terrace

- Common cooking facilities

- Sauna

- 4 guest apartments

- Ground level parking with communal yard elevated above

Bo01 – The “City of Tomorrow”

Malmö, Sweden | 2001 | Klas Tham, City of Malmö Planning Office

Unique Features

Bo01 is a sustainable neighborhood, built on a formal industrial site. It was the first in a series of projects that stemmed from a European Housing Exposition in 2000. The site hosts 1,425 residential units, along with commercial, service, and educational spaces and recreational areas. Most of the site’s energy needs are met on site, but it is connected to the city’s grid, taking more energy when needed and feeding extra energy back into the grid when there is an overflow. The project also encourages sustainable living, with amble paths for walking and cycling, no roads in the neighborhood, and easy access to the bus system.

Key Elements

- 100% renewable energy

- Wind turbine system and photovoltaic panels

- Rainwater purification

- Green roof

- Mix of unit sizes and ownership types

- Stormwater management through rain gardens, small ponds, and canals

Hammarby Sjöstad

Stockholm, Sweden | 2004-2016 | Urban Planning and Environmental Coord Committee, Stockholm Water Company

Unique Features

Hammerby Sjöstad is situated along waterfronts in a formal industrial sector of Stockholm, Sweden. The site is optimized to allow many residents to enjoy views of the water. The project uses cutting-edge sustainable technology, such as new types of fuel cells, solar cells, and solar panels. Another system they are experimenting with is biogas cookers. The biogas produced by one family, which is formed in the waste water treatment process, is often close to enough to fuel the family’s cooking energy needs.

Key Elements

- PV panels and fuel cells

- Waste water treatment, with the recycling and use of sludge and biogas

- Rainwater runoff treatment

- Self-monitoring energy and water consumption website for residents

Bedzed: “Bedzed – The UK’s First Large-Scale Eco-Village.” Bioregional, www.bioregional.com/projects-and-services/case-studies/bedzed-the-uks-first-large-scale-eco-village.

Kalkbreite: “Welcome to the Kalkbreite Cooperative,” www.kalkbreite.net/en/.

Grow Community: “Grow Community,” davisstudioad.com/?portfolio=grow-community-2.

Sonnenschiff and Solarsiedlung: Rolf Disch. The Sun ShIp: An Ecological Model for the Future, The Solar Settlement.

The Village on False Creek: “The Village on False Creek.” Merrick Architecture, merrickarch.com/work/village-false-creek/.

Gwl Terrein Housing Development: “GWL Terrain: Amsterdam’s First Car-Free Neighborhood.” Sustainable Amsterdam, sustainableamsterdam.com/2016/02/gwl-terrain-amsterdams-first-car-free-neighborhood/.

Note: Architects for this project include: DKV Architects, Neutelings Riedijk Architecten BV, Kees Christiaanse Architects & Planners, CASA Architects, Paul Westerman, Meyer & Van Schooten Architects BV, and Atelier Zeinstra van der Pol.

Titletown District: “Green Bay Packers Titletown District Sledding Hill / Rossetti,” https://www.archdaily.com/899041/green-bay-packers-titletown-district-sledding-hill-rossetti?ad_source=search&ad_medium=search_result_all & “Aroens Hill,” https://www.rossetti.com/work/project/ariens-hill

Pierhouse & 1 Hotel Brooklyn Bridge: “Pierhouse & 1 Hotel Brooklyn Bridge / Marvel Architects.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 31 Aug. 2019, www.archdaily.com/922623/pierhouse-and-1-hotel-brooklyn-bridge-marvel-architects?ad_source=search&ad_medium=search_result_projects.

Liberty Center: “Liberty Center.” Architectmagazine.com, 2014, www.architectmagazine.com/project-gallery/liberty-center-5933.

BIGyard: “BIGyard / Zanderroth Architekten,” https://www.archdaily.com/793287/bigyard-zanderroth-architekten

BO01: Austin, Gary. “Case Study and Sustainability Assessment of Bo01, MalmÖ, Sweden.” Journal of Green Building, vol. 8, no. 3, 2013.

Hammerby Sjostad: “Hammarby Sjöstad, Stockholm, Sweden.” Urban Green-Blue Grids for Resilient Cities, Creative Industries Fund, www.urbangreenbluegrids.com/projects/hammarby-sjostad-stockholm-sweden/.

All photos sourced from the internet

Recent

- Ideas at Play: How Adults Can Design for Children

- Designing for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- Trauma-Informed Design: Inclusive Buildings for All

- Neuroscience and Architecture: What Science Teaches Us About Designing Buildings for Mental Health and Well-Being

- Human-Centered Design: Making the Built Environment Work for Everyone

Other Relevant Insights

We’re proud to be in good company.

We love being part of the community that’s bringing good design to good people. That’s why we contribute to and participate in these organizations – so we can bring the best emerging ideas to you.

Get In Touch

Let us bring your vision to life.

A beautiful space that fits your best life. A sustainable build. A fun and easy design process. We’re with you every step of the way – from the beginning dream to the finished project!